Sexual offending, or the commission of sexual offences, is a complex problem, whose causes are multi-factorial. People who commit sexual assault do so for a diversity of reasons. Nevertheless, certain categories of perpetrators share certain characteristics to a greater extent than people who do not commit sexual assault.

Who commits sexual assault? And why do they commit it?

- Due to the wide range of sexually aggressive behaviours and the many different underlying motivations, it is impossible to establish a typical profile of a perpetrator of sexual assault.

- That being said, deviant sexual interests (paraphilia) and cognitive distortions are two essential factors that explain why people commit sexual assault.1

- Three categories of perpetrators can be identified depending on the nature of the sexual assaults they commit, their relationship to the victim, their age and the age of the victim.4 These categories are: perpetrators of sexual abuse against children, including intrafamilial and extrafamilial abusers; perpetrators of sexual assault against adults, usually women; and minors who commit sexual assault. However, these categories are not mutually exclusive since, for example, the same individual may assault both female adolescents and adult women.4,5

Perpetrator, predator or sex offender?

The term perpetrator refers to any person who commits a sexual assault, regardless of whether the victim is a minor or an adult, whereas sexual offender refers to someone who has been convicted of a criminal sexual offence.

As for the term sexual predator, it is usually employed pejoratively or to create a vivid impression when speaking of an individual who has committed several sexual assaults.6 As such, this term relies on an analogy with the hunter who stalks and hunts down prey to portray an individual who allegedly is constantly “on the prowl” for potential targets to sexually assault. However, such behaviour is typical of only a minority of perpetrators.6 Experts may refer to “predatory behaviour” among serial perpetrators of sexual assault as a way of discussing the methods used to spot and attack a potential unknown victim.7 Nowadays, the term online predator is used to refer to people who contact a minor over the Internet for the purpose of committing a sexual offence (i.e. luring a child).

Inappropriate use of the term sexual predator can create the false impression among the public that most sexual assaults are committed by people who are not known to the victim and who seek out and choose their victim at random. In reality, however, this is the case of only a very small proportion of perpetrators.Studies on perpetrators of sexual assault: methodology

Studies on the characteristics of sexual assault perpetrators have focused mainly on men who have been convicted of sexual offences or who are part of treatment groups mandated by law. The characteristics reported in these studies are thus not representative of sexual assault perpetrators as a whole. Moreover, since this research is based on self-administered questionnaires, the answers may be biased.2,3 Lastly, given that women who commit sexual assault make up only a small percentage of the prison population, they have been studied to only a limited extent.

Perpetrators of child sexual abuse

Child sexual abusers or pedophiles?

The term child sexual abuser refers to a person who sexually abuses minors. However, the abuser may or may not meet the diagnostic criteria of pedophilia. The term pedophile is used, following a clinical diagnosis by a qualified professional, to refer to an individual who is 16 years of age or older, who has an exclusive or non-exclusive sexual attraction to prepubescent children (usually under 13 years of age) and who meets a specific set of criteria.8 The diagnostic criteria for pedophilia have been criticized on several occasions, particularly the criterion whereby a person has to have sexually abused children for a diagnosis of pedophilia to be made.9

The term pedophile is often mistakenly used in the general population to refer to any person who sexually abuses children,2 whereas, in reality, only a minority of perpetrators of child sexual abuse meet the diagnostic criteria of pedophilia.10Child sexual abusers who meet the diagnostic criteria of pedophilia are more likely than their non-pedophile counterparts to have abused young people, males, and people from outside their family, and to have abused a number of children.5.

Characteristics of child sexual abusers

- Child sexual abusers are not a homogeneous group. They can be either male or female; heterosexual, homosexual or bisexual; in a couple or single; from any ethnic background; or from different socio-economic backgrounds.2

- Although their motivations vary, child sexual abusers share certain personal characteristics more often than non-abusers do:

| Personal characteristics of child sexual abusers1,4,5,2,11 | |

|---|---|

| Poor social skills | Strained relationships with adults |

| Feelings of powerlessness | Unsatisfactory relationships with adults |

| Low self-esteem, self-devaluation | Vulnerability in regard to their masculinity |

| Feelings of humiliation | Loneliness |

| Emotional attachment problems | Sexual problems |

A word of caution

The personal characteristics identified above to describe child sexual abusers are more likely to be found among people who have committed sexual abuse. However, it is not because a person displays these characteristics that he or she is an abuser or will commit sexual abuse.

-

Gender of child sexual abusers

- Most minors who are victims of sexual abuse are victimized by males. In fact, according to available studies, the proportion is 85% or more. The proportion is even higher in the case of girls.11 For more information, see the statistics on child sexual abuse.

- Even though men make up the majority of perpetrators of child sexual abuse, it appears that a large number of abusers are female. Men victimized in childhood report that they were abused by a woman in nearly 40% of cases.12 For more information, see the fact sheet on sexual assault by women.

-

Age of child sexual abusers

- A large proportion of child sexual abuse seems to be committed by minors. Studies have estimated, using various victim samples, that 40% to 51% of child sexual abuse is perpetrated by people under 20 years of age and that 13% to 18% is committed by children under the age of 13.13 For more information, see the statistics on child sexual abuse.

-

Relationship of abusers to their victims

- Perpetrators of child sexual abuse are very often known to their victims (in 75% to 90% of reported cases).11 For more information, see the statistics on child sexual abuse.

- Close to one quarter of victims surveyed during a Québec population survey reported that they had been abused by a member of their immediate family, either a parent or a sibling.14

- A number of data show that stepfathers are more likely than biological fathers to sexually abuse a child in their family.13

- Many studies report that sexual abuse is committed more often by a sibling than by a paternal figure.11,13

-

Mental health of child sexual abusers

- A large proportion of perpetrators of child sexual abuse who have been diagnosed as pedophiles have had a mental health problem at some point in their life (a mood disorder in 60% to 80% of cases, an anxiety disorder in 50% to 60% of cases and a personality disorder in 70% to 80% of cases).2

- A few studies have shown that a large proportion of perpetrators diagnosed as pedophiles have also received a diagnosis of substance abuse or dependence at some point in their life (in 50% to 60% of cases).5,2

-

Cognitive distortions of child sexual abusers

Cognitive distortions correspond to faulty thinking that reflects unrealistic or distorted perceptions of reality. They are found among many perpetrators of sexual abuse and are expressed in the form of justifications for the offences they commit.1 They are formulated in such a way as to deny, minimize, rationalize or even perpetuate the perpetrator’s behaviour.2 Below are some of the cognitive distortions often encountered among child sexual abusers:

- “The child consented to the sexual activity because she did not say ‘no’ and derived pleasure from the abuse.”

- “I’m contributing to the child’s sex education.”

- “I’m very gentle and never use violence; it’s not sexual abuse.”

- “The child wanted me to do it because she was the one who suggested we get closer.”

Child sexual abuser typologies

Statistical methods are used to generate perpetrator profiles based on the characteristics of small samples of convicted sex offenders. Caution must be exercised in using these profiles because they are not necessarily representative of all perpetrators and are not mutually exclusive.4

- Despite the range of child sexual abuser profiles, various typologies have been proposed over the past 30 years to classify child sexual abusers on the basis of their personal characteristics and/or those of their victims, and their motivations for committing sexual abuse.

- The most popular typologies are those developed by Groth (1978)15 and, more recently, by Knight and Prentky (1990).16

-

- Groth’s typology proposes two types of perpetrator: the fixated perpetrator, who has a persistent and compulsive attraction to children, and the regressed perpetrator, whose sexually abusive behaviour is triggered by certain specific situations and external stressors.4

- Knight and Prentky’s typology identifies several subtypes of child sexual abusers based, in particular, on the degree to which they are attracted to children, their level of social competence, the amount of non-sexual contact they seek with children and the amount of physical violence they use in abusing children.4

- Groth’s typology proposes two types of perpetrator: the fixated perpetrator, who has a persistent and compulsive attraction to children, and the regressed perpetrator, whose sexually abusive behaviour is triggered by certain specific situations and external stressors.4

- In Québec, experts have developed three different profiles of child sexual abusers based on the abusers’ personal characteristics and the characteristics of the abuse they commit.17 These profiles were defined through criminal profiling of convicted child sex offenders in Québec. Profiling of this type is the main investigative tool for identifying suspects or guiding criminal investigations.17 The three profiles developed are: “isolated pedophile”, “orderly pedophile” and “festive pedophile”.

-

Isolated pedophile

This profile accounted for one third of a sample selected for the purposes of a study on incarcerated child sexual abusers.

Lifestyle

- Is usually not involved in a romantic relationship and lives alone

- Does not go to bars or use alcohol or drugs Has an education and a job

- Is premediated but does not involve coercion

- Is intended to establish a climate of trust so that an intimate relationship can be developed with the victim

- More often targets male victims

- Consists primarily of sexual acts involving fellatio and masturbation

-

Orderly pedophile

This profile accounted for one quarter of a sample selected for the purposes of a study on incarcerated child sexual abusers.

Lifestyle

- Rarely lives alone and is in a couple relationship in 50% of cases

- Seems to lead a quiet, orderly life (rarely goes to bars, goes to bed early, has a job and is a homeowner

- May use alcohol before committing the abuse, but does not use drugs

- Is premeditated but does not involve a pre-selected victim

- Often involves viewing pornography beforehand

- Is often perpetrated by someone who is close to the victim or by a member of the victim’s family

- Consists primarily of sexual acts involving penetration

-

Festive pedophile

This profile accounted for 43% of a sample selected for the purposes of a study on incarcerated child sexual abusers.

Lifestyle

- Is rarely involved in a romantic relationship

- Is a night owl and often goes to bars

- Seeks immediate satisfaction

- Uses drugs and alcohol regularly

- Rarely owns a house and is often unemployed

- Lacks premeditation

- Often involves coercion

- Is often perpetrated while intoxicated

- Consists primarily of sexual acts involving penetration

Strategies used by perpetrators to commit child sexual abuse

A number of studies have shed light on the strategies used by perpetrators in order to abuse children.

Child sexual abusers rarely use physical coercion to commit their crimes. In fact, many seek to establish a emotional relationship with the child, and this has an impact on the strategies they employ to commit the abuse.4,2

- A large majority of sexual offences against children (between 70% and 80%) are premediated, which runs counter to the notion that uncontrolled impulses and lack of control are what drive perpetrators of child sexual abuse.2

- People who abuse children from outside the family usually try to place themselves in a position of authority where they will be in contact with children who are not under adult supervision: for example, they baby-sit, work as volunteers with children or coach sports teams. They then try to win the trust of the children and their parents.2

- On account of their poor social skills, many child sexual abusers are at ease in relationships with children who are passive, psychologically dependent and easy to manipulate.4 Indeed, these characteristics are sought by certain perpetrators, and the children who display them can be more vulnerable to sexual abuse.2,11

- Most child sexual abusers create a climate that breaks down the child’s resistance and thus enables them to victimize the child. This preparation strategy allows them to manipulate potential victims into agreeing to the sexual activities the abusers initiate. Below is a list of strategies employed by perpetrators, the majority of which do not involve coercion:1,4,2,17.

- Creation of a state of emotional dependence/manipulation

- Seduction

- Persuasion and manipulation

- Games

- Gradual desensitization

- Gifts, privileges

- Threats

- Physical or verbal coercion

Perpetrators of adult sexual assault

Characteristics of perpetrators of sexual assault against women

- People who sexually assault adult females are not a homogeneous group.4 Their wide range of profiles is due to the diversity of their motivations for committing sexual assault and their divergent modus operandi.18

-

Nonetheless, people who sexually assault women are more likely to have certain personal characteristics:

Personal characteristics of perpetrators of sexual assault against women4 In childhood Physical abuse Family problems In adulthood Belief in myths about rape Acceptance of violence (approval) Strong identification with male stereotypes Negative view of women Low self-esteem Difficulty managing aggression and anger Substance abuse Mood disturbances (sadness, anger, fear, anxiety)

It appears that sexual crimes represent only part of the criminal activities of perpetrators of sexual assault against women, and they are mainly the result of generalized deviant behaviour.1.

Experts have identified two important factors that lead people to sexually assault adult females: deviant sexual interests and cognitive distortions.1

-

Deviant sexual interests

People who sexually assault women are more likely to be interested in non-consensual sexual relations involving physical violence or humiliation1.

-

Cognitive distortions

Cognitive distortions correspond to faulty thinking on the part of perpetrators that reflects unrealistic or distorted perceptions of reality. Perpetrators use these distortions to justify the crimes they commit.

Below are some examples of the cognitive distortions concerning women and sexual assault encountered among people who victimize women.

- “Women enjoy forced sexual activities.”

- “It was the victim who initiated the contact.”

- “Women control, reject and humiliate me.”

- “Committing a crime is a fair way to compensate for past injustices.”

Motivations of perpetrators of sexual assault against women

The motivations for sexually assaulting adult females vary. Therefore, there is a diversity of typologies of perpetrators of sexual assault against women.4 Male perpetrators are driven mainly by a desire for power and control rather than by their sexual impulses, especially in situations where the victim is their spouse or an acquaintance.4

Typologies of perpetrators of sexual assault against women

Perpetrator typologies can be a useful tool for conducting police investigations, doing clinical assessments and treating perpetrators, but they must be used with caution. Such profiles are not mutually exclusive and sexual assault perpetrators rarely commit only one type of sexual assault.4

- Over the past 30 years, several authors have proposed typologies of perpetrators of sexual assault against women based on the perpetrators’ personal characteristics, motivations for committing sexual assault, modus operandi, triggers, and other antisocial behaviour (e.g. Groth, 1979; Knight and Prenty, 1990; Barbaree, 1994).4

- The following table summarizes the main typologies proposed by various authors on the basis of perpetrators’ personal characteristics, motivations and modus operandi.4,18

-

Summary of typologies of perpetrators of sexual assault against women Compensatory Sadistic Angry

(power/control)Opportunistic General lifestyle Poor social skills

Show little aggressive behaviourLow self-esteem

Social isolation

Opposed to authority

Self-mutilation

Often psychopathicTemper tantrums

Substance abuseNo major problems

Adventure-seeking lifestyle

Difficulties with impulse controlLove and sex life May have seduction problems

Doubt their desirability

Lack the ability to form a relationship with a partner of the same ageDeviant or non-deviant sexuality

Focused on sexuality (e.g. compulsive masturbation)Non-deviant sexuality

Diverse and intense sexuality (e.g. pornography, erotic bars, prostitutes, etc.)Non-deviant sexuality

Sexual dissatisfaction (nature and frequency of sexual relations)Life circumstances in the months prior to an offence Feelings of inadequacy

Conflicts with women

Loneliness

Low self-esteemConflicts with authority

Conflicts with womenMotivations Use aggressive behaviour to offset fears about their masculinity

Achieve sexual gratification through the victim’s pain and fear

Desire power and dominance over the victim

May be motivated by a desire to humiliate the victim

Often motivated by anger and rageMotivated by immediate sexual gratification

Characteristics of sexual assaults committed and modus operandi Use only as much force as necessary to achieve sexual gratification

May flee if the victim cries out or defends herselfPlan their crimes in great detail

Usually victimize strangers

Show little or no remorse

Use a high level of violence that can lead to sexual murderExpress aggression sexually

May premeditate the sexual assault with a specific victim in mind or act impulsively against people who have made them angryMay commit sexual assault in the course of another crime

Based on Robertiello and Terry (2007) and Proulx, St-Yves, Guay and Ouimet (1999)

Research on perpetrators of sexual assault against women

The characteristics of people who sexually assault adults have been studied using inmates who have raped women from outside their family. However, assaults of this type account for only a portion of all sexual assaults against adults. In fact, statistics on adult sexual assault show that men are also victimized and that many assaults are perpetrated by current or former spouses, intimate partners or acquaintances. Moreover, most sexual assaults of adults take place in private settings.

To learn more about the characteristics of men who engage in sexual violence in a marital context, see the section on spouses with violent behaviour in the Trousse média sur la violence conjugale (media kit on spousal violence). (Available in French only)

Minors who commit sexual assault

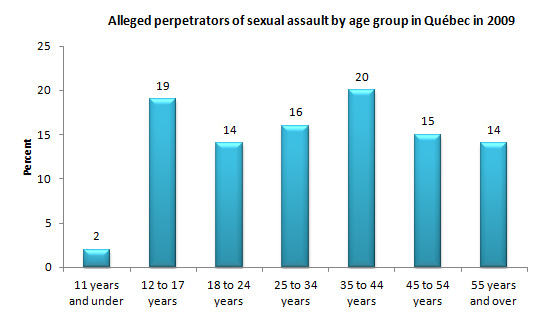

- Minors are responsible for a large number of sexual assaults. Sexual assault data compiled by police services in both Québec and Canada show that young people under 18 form the age group with the largest number of perpetrators.19,20,21

- Many adults who commit sexual assault say that they committed their first assault when they were adolescents (between 50% and 80% depending on the study). This demonstrates the importance of taking action early on to prevent adolescent perpetrators from committing other sexual assaults later in life.1

Sexual abuse by children

Children under 12 years of age sometimes commit sexual abuse, usually against younger children. In Québec in 2009, 2% of alleged perpetrators who were reported to the police were under the age of 12. This proportion underestimates the extent of sexual abuse by children and reflects the fact that such situations are rarely brought to the attention of the authorities given that perpetrators under 12 cannot be charged with an offence.19 According to population studies, the proportion of sexual abuse committed by children lies somewhere between 10% and 18%.22

That being said, there is a consensus that children should not be labelled as sexual abusers, but should instead be considered, on account of their age and level of development, to have sexual problems directed toward others.22,23 Nonetheless, children who are victimized by other children can be considered sexual abuse victims and they may develop sequelae (i.e. after-effects).

Treatment programs have been designed in recent decades for children with sexual behaviour problems, and many of these programs have proven to be effective.23,1

For more information on children with sexual behaviour problems, visit the Centre d’expertise Marie-Vincent website

Characteristics of adolescents who commit sexual assault

- Adolescent perpetrators of sexual assault who are known to the authorities form a heterogeneous group, not only with regard to the sexual acts they commit and the victims they choose, but also with regard to their personal characteristics.24,25

- Adolescents victimize people of all ages, be they males, females, people they know or strangers.1,4

- Adolescent perpetrators share more similarities than differences with adolescent non-sex offenders.24

- Adolescents who sexually abuse a sibling more often have behavioural disorders, learning disabilities, attention deficit disorder with or without hyperactivity (ADHD), and mood and anxiety disorders.26

| Personal characteristics of adolescent perpetrators of sexual assault1,4,11,27 | |

|---|---|

| Early breakdown in the continuity of paternal care | Sexual abuse (in roughly 30% of cases) and physical abuse in childhood |

| Learning disorders and academic retardation | Alcohol and drug use during assaults |

| Social isolation (especially child abusers) | Social maladjustment and asocial behaviour |

| Depressive symptoms | Regular viewing of pornography |

| Family dysfunction | Behavioural disorders |

| Social skill deficits | |

Behavioural disorder or indictable offence?

When a minor commits a sexual assault, two laws with different objectives are brought into play: the Youth Protection Act (YPA) and Youth Criminal Justice Act(YCJA).1 The YPA ensures the security and development of children, particularly those with a serious behavioural disturbance. Therefore, minors who sexually abuse children or commit offences involving “less serious” forms of sexual assault are more likely to be taken in charge under subparagraph f of the second paragraph of section 38 concerning serious sexual disturbance. This type of disturbance refers to “a situation in which a child behaves in such a way as to repeatedly or seriously undermine the child's or others' physical or psychological integrity”.

Minors who have committed “more serious” forms of sexual assault or who have sexually assaulted adolescents or adults are more frequently taken in charge under the YCJA. This Act sets out the principles, rules of procedure and sentences applicable under federal legislation, such as the Canadian Criminal Code, to young people aged 12 to 17 at the time when they commit an offence. In such cases, the matter may be referred to the court and the young person must appear before the Youth Division. Referral to the court is automatic in the case of sexual assault with a weapon or aggravated sexual assault. For more information on sexual assault legislation, see the Legal Framework section.Typologies of adolescent perpetrators of sexual assault

A number of typologies have been proposed to describe the various profiles of adolescents who commit sexual assault. However, two main categories can be defined based on the age of the victims: adolescents who sexually abuse children and those who sexually assault other adolescents or adults.4

-

Adolescents who sexually abuse children

- Adolescents in this category target both girls and boys (20% to 30% boys) and often their siblings, other children in their extended family or children under their responsibility (e.g. children they are baby-sitting).

- They rely on opportunity, trickery, manipulation, threats and, more rarely, force.4

- They often have low self-esteem and are more likely to lack social skills and show signs of depression.4

-

Adolescents who sexually assault other adolescents or adults

Adolescents who sexually abuse siblings

- 10% to 35% of sexual assaults by adolescents are committed within families against brothers and sisters or half-brothers and half-sisters.1

- The family environment of adolescents who sexually abuse siblings seems to be disturbed to a greater extent than that of adolescents who victimize individuals from outside the family or who have never committed sexual abuse.

- In addition, research on the personal characteristics of adolescents who abuse siblings has shown primarily that they are diagnosed as having psychiatric problems more often than adolescents who victimize individuals from outside the family or who have never committed sexual assault.26

Last update: October 2016

- Lafortune, D., Proulx, J. and Tourigny, M. (2010). Les adultes et les adolescents auteurs d'agression sexuelle. In Le Blanc, M. and Cusson, M., eds., Traité de criminologie empirique (4th ed.) (pp. 305-336). Montréal: Les Presses de l'Université de Montréal. (Available in French only)

- Hall, R.C.W. and Hall, R.C.W. (2009). A profile of pedophilia: Definition, characteristics of offenders, recidivism, treatment outcomes, and forensic issues. Focus: The Journal of Lifelong Learning in Psychiatry, 7(4): 522-537.

- Murray, J.B. (2000). Psychosocial profile of pedophiles and child molesters. The Journal of Psychology, 134(2): 211-224.

- Robertiello, G. and Terry, K.J. (2007). Can we profile sex offenders? A review of sex offender typologies. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 12: 508-518.

- Seto, M.C. (2008). Pedophilia and sexual offending against children: Theory, assessment, and intervention. Washington (DC): American Psychological Association.

- Filler, D. (2001). Making the case for Megan’s law: A study in legislative rhetoric. Indiana Law Journal, 76 (2): 315-366.

- Beauregard, E. and Rossmo, K. (2008). Geographic profiling and analysis of the hunting process used by serial sex offenders. In M. St-Yves and M. Tanguay, eds., The Psychology of Criminal Investigations: The Search for the Truth (pp. 529-554). Toronto: Carswell.

- American Psychiatric Association (2000). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed., text revision). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

- Blanchard, R. (2009). The DSM diagnostic criteria for pedophilia. Archives of Sexual Behaviour, published online: 16 September 2009.

- Marshall, W.L. (1997). Pedophilia: Psychopathology and Theory. In D.R. Laws and W. O’Donohue, eds., Sexual Deviance: Theory, Assessment, and Treatment (pp. 152-174). New York: Guilford.

- Tourigny, M. and Baril, K. (2011). Les agressions sexuelles durant l’enfance : Ampleur et facteurs de risque. In M. Hébert, M. Cyr, and M. Tourigny, eds., L’agression sexuelle envers les enfants Tome 1 (pp. 7-42). Québec: Presses de l’Université du Québec. (Available in French only)

- Dube, S.R., Anda, R.F., Whitfield, C.L., Brown, D.W., Felitti, V.J., Dong, M. and Giles, W.H. (2005). Long-term consequences of childhood sexual abuse by gender of victim. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 28(5): 430-438.

- Wolfe, V.V. (2007). Child sexual abuse. In E.J. Mash and R.A. Barkley, eds., Assessment of Childhood Disorders (4th ed.) (pp. 685-748). New York: Guilford Press.

- Tourigny, M., Hébert, M., Joly, J., Cyr, M. and Baril, K. (2008). Prevalence and co-occurrence of violence against children in the Quebec population. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 32(4): 331-335.

- Groth, A.N. (1978). Guidelines for the assessment and management of the offender. In A.W. Burgess, A.N. Groth, L.L. Holmstrom and S.M. Sgroi, eds., Sexual Assault of Children and Adolescents (pp. 25-42). Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

- Knight, R.A. and Prentky, R.A. (1990). Classifying sexual offenders: The development and correlation of taxonomic models. In W.L. Marshall, D.R. Laws and H.E. Barbaree eds., Handbook of Sexual Assault: Issues, Theories and Treatment of the Offender (pp. 23-52). New York: Plenum Press.

- Blanchette, C., St-Yves, M. and Proulx, J. (2008). Sexual aggressors: Motivation, modus operandi, and lifestyle. In M. St-Yves and M. Tanguay, eds., The Psychology of Criminal Investigations: The Search for the Truth (pp. 409- 426). Toronto: Carswell.

- Proulx, J., St-Yves, M., Guay, J.P. and Ouimet, M. (1999). Les agresseurs sexuels de femmes. Scénarios délictuels et troubles de personnalité. In J. Proulx, M. Cusson and M. Ouimet, eds., Les violences criminelles (pp.157-185). Québec: Les Presses de l’Université Laval. (Available in French only)

- Ministère de la sécurité publique du Québec. (2012). Infractions sexuelles au Québec : Faits saillants 2010. Québec: Gouvernement du Québec. (Available in French only)

- Ministère de la sécurité publique du Québec. (2011). Statistiques sur les agressions sexuelles au Québec 2009. Québec: Gouvernement du Québec. (Available in French only)

- Brennan, S., and Taylor-Butts, A. (2008). Sexual Assault in Canada 2004 and 2007. Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

- Gagnon, M.M. and Tourigny, M. (2011). Les comportements sexuels problématiques chez les enfants âgés de 12 ans et moins: Évaluation et traitement. In M. Hébert, M. Cyr, and M. Tourigny, eds., L’agression sexuelle envers les enfants Tome 1 (pp. 333-362). Québec: Presses de l’Université du Québec. (Available in French only)

- Association for the Treatment of Sexual Abusers - ATSA (2006). Report of the Task Force on Children with Sexual Behavior Problems.

- Grant, J., Indermaur, D., Thornton, J., Stevens, G., Chamarette, C. and Halse, A. (2009). Intrafamilial adolescent sex offenders: psychological factors and treatment issues. Research report. Criminology Research Council.

- Lagueux, F. and Tourigny, M. (1999). État des connaissances au sujet des adolescents agresseurs sexuels. Québec: Ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux. (Available in French only)

- Salazar, L.F., Camp, C.M., DiClemente, R.J. and Wingood, G.M. (2005). Sibling incest offenders. In T.P. Gullotta and G.R. Adams, eds., Handbook of adolescent behavioral problems: Evidence-based approaches to prevention of adolescent behavioral problems (pp. 503-518). New York, NY: Springer.

- Grant, J., Indermaur, D., Thornton, J., Stevens, G., Chamarette, C. and Halse, A. (2009). Intrafamilial adolescent sex offenders: psychological factors and treatment issues. Research report. Criminology Research Council.