What do we know about people who have been sexually assaulted and the sexual assaults they have experienced?

- Even though various personal factors may be associated with an increased risk of being a victim of sexual assault, there is no typical profile of a sexual assault victim.

- Nonetheless, certain personal characteristics are found more often among children, women and men who have been victimized. Moreover, the nature and context of sexual assault situations can be described on the basis of a range of data.

- Certain characteristics of sexual assault can be identified and used to describe the sexual assault situations experienced by victims.

- Few sexual assault victims disclose the acts they have been subjected to, while those who do disclose them, particularly children, delay in doing so, thus depriving themselves of the protection and services they might receive.

To learn about the impact of sexual assault on victims, see the Consequences section.

Child victims of sexual abuse

For more information on statistics pertaining to the prevalence and characteristics of child sexual abuse, see the Statistics section.

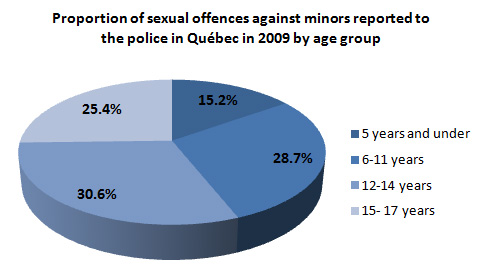

- Children and adolescents are the primary targets of sexual abuse. They were the victims of two thirds (66%) of all sexual offences recorded by police in Québec in 2010.1

- There is no typical profile of a child victim of sexual abuse. However, the context and nature of the abuse experienced by children can be described on the basis of certain data.

-

In 2008, the Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect (CIS-2008) documented nearly 16 000 maltreatment situations reported to child welfare services in Canada. The data collected during the study can be used to describe the characteristics of the sexual abuse experienced by children whose cases were selected for investigation by Canadian child welfare services. To learn more

According to this data:2

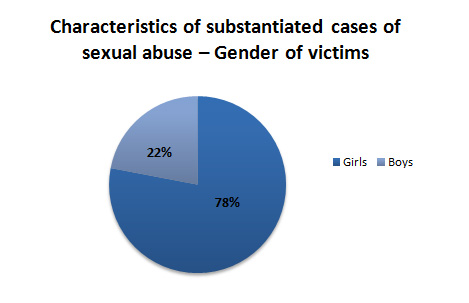

- The victim was a girl in most substantiated cases of sexual abuse (78%).

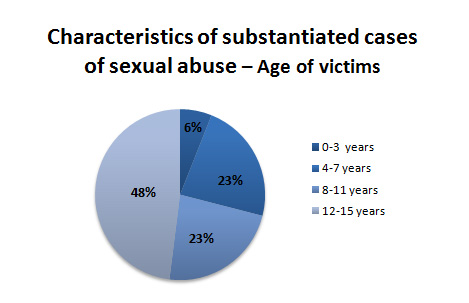

- Nearly half (48%) of the victims of substantiated sexual abuse were 12 to 15 years old.

- More than half (51%) of substantiated cases of sexual abuse involved multiple incidents.

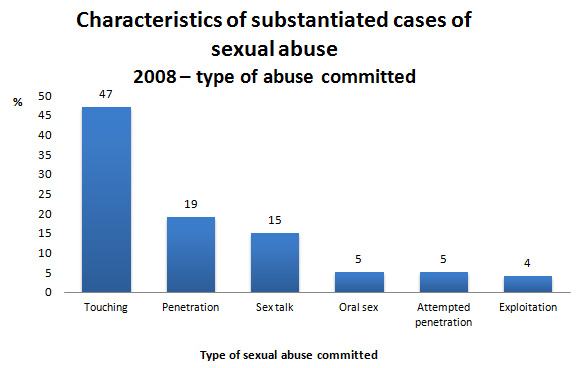

- Most substantiated cases (50%) of sexual abuse involved touching.

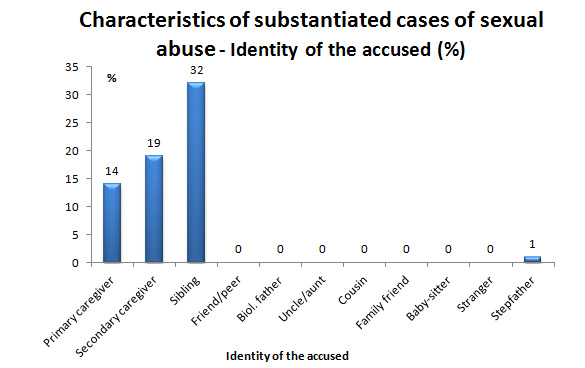

- In 28% of cases, the perpetrator was a caregiver who lived with the child.

- In nearly one third (32%) of cases, the victims were sexually abused by a sibling.

Source: CIS-2008

-

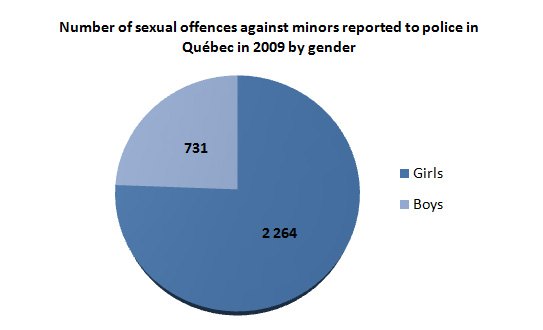

Sexual offences recorded by police services in Québec (UCR2) in 2009 and 2010 can be used to describe the sexual abuse against children and adolescents that was reported to the authorities for those years. To learn more

According to the data recorded by police:

- In 2010, the number of sexual offences against girls was three and a half times higher (n=2 621) than the number against boys (n=749).1

- In 2010, girls were more often sexually abused during adolescence (61%), whereas boys were more often victimized before the age of 12 (62%).8

- Sexual assault with a weapon(level 2) or aggravated sexual assault (level 3) accounted for less than 1% of all sexual offences against minors recorded in 2009.8

- 87% of young people who were victims of sexual abuse in 2010 knew the accused. In roughly half of the cases (48%), the perpetrator was a family member.1

- Children aged 11 or under were victimized by a member of their immediate or extended family more often than were young people aged 12 to 17 (65% compared to 36%).1

Source: UCR2 – MSP 2009

- A large number of child sexual abuse victims also seem to have experienced other forms of violence.

- According to several studies, 16% of people who were sexually abused as children also experienced one other form of maltreatment during childhood (physical abuse, psychological abuse, exposure to spousal violence, or neglect), while between 5% and 17% experienced two other forms of maltreatment.3

- In Québec, 19% of people who reported having been sexually abused as children also reported that they were victims of physical violence before the age of 18; 14% reported that they had experienced psychological violence as well in childhood.4

- In cases where allegations of sexual abuse were deemed founded by child welfare services in Québec and Canada between 1998 and 2003, assessments confirmed that between 25% and 49% of the children concerned had experienced one other form of maltreatment, including physical abuse, psychological abuse, neglect and exposure to spousal violence.5,6,7

Gender-based differences among child victims of sexual abuse

Several scientific studies of child sexual abuse victims as well as statistics from youth protection services and police indicate that girls and boys differ with regard to the nature of the sexual abuse they experience.

- Girls are victims of intrafamilial sexual abuse more often than boys are.9

- Boys are victimized by strangers more often than girls are.9

- Compared to girls, boys are sexually abused over a shorter period of time and experience fewer incidents of sexual abuse.10

- Girls are more often victims of sexual abuse during adolescence, whereas boys are more often victimized during childhood (0-12 years of age).8

- In cases of sexual abuse substantiated by child welfare services in Canada, the number of girl victims of penetration (12.5%) is higher than the number of boy victims (4.2%).11

Women victims of sexual assault

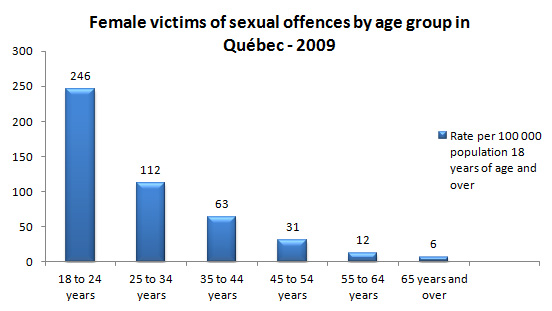

- Women are the primary victims of sexual assault among adults aged 18 and over. In Québec, females account for more than 9 in 10 victims of sexual offences.1

-

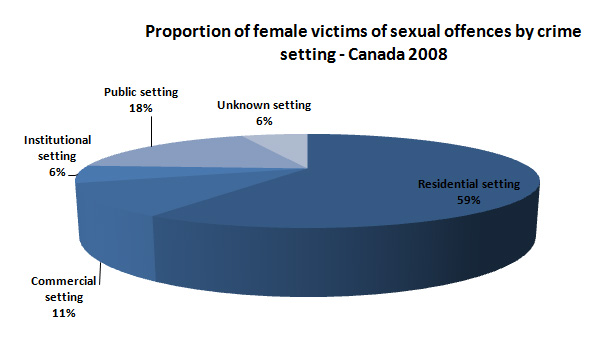

There is no typical profile of a female victim of sexual assault. However, statistics on sexual offences recorded by police services in Québec and Canada and victimization survey data reveal some of the characteristics of women who have been sexually assaulted and can be used to describe the assaults they experienced. To learn more

According to this data:

- Among adult females, the age group with the highest number of sexual offence victims in Québec in 2009 consisted of women between the ages of 18 and 24.8

- 38% of sexual offences against women in Canada in 2008 involved injuries.12

- 3.2% of female victims of sexual offences in Québec in 2009 experienced aggravated sexual assault or sexual assault with a weapon.8

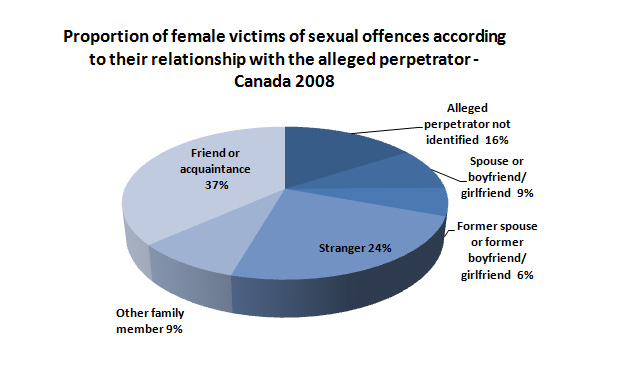

- Sexual offences against women in Canada in 2008 occurred for the most part (59%) in a residential setting.12

- Most female victims of sexual offences in Canada in 2008 (37%) were assaulted by a friend or an acquaintance.12

Source : UCR2 – MSP 2009

Source : UCR2 – Statistics Canada

Men victims of sexual assault

The myths and prejudices associated with male sexuality and sexual assault against men are an obstacle to disclosure, with the result that statistics are not very reliable. Experts believe that official statistics underestimate the number of adult males who are victims of sexual assault.13

- There has not been very much research on sexual assault of adult males. In fact, most studies have focused on sexual abuse of boys.13

- Males account for a smaller proportion of adult victims of sexual assault compared to females. In 2010, they accounted for 3% of all sexual offences reported to police in Québec.1

- In a 2009 survey of Canada’s adult population, 30% of sexual assaults reported by respondents had been committed against men. However, according to data compiled by police services, men accounted for only 8% of adult victims of sexual offences, suggesting that adult males are underrepresented among sexual offence victims.

-

As in the case of women, there is no typical profile of a male victim of sexual assault. However, statistics on sexual offences recorded by police services in Québec and Canada and victimization survey data reveal some of the characteristics of men who have been sexually assaulted and can be used to describe the assaults they experienced. To learn more

According to this data:

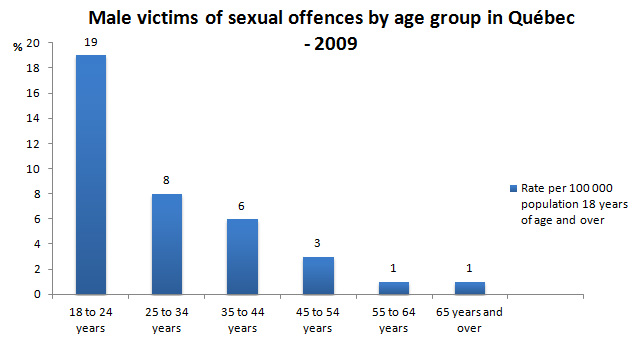

- Among adults, the 18-24 age group accounted for the highest number of male victims of sexual offences in Québec in 2009.8

- 30% of sexual offences against men in Canada in 2008 involved injuries.14

- 1.5% of male victims of sexual offences in Québec in 2009 experienced aggravated sexual assault or sexual assault with a weapon.8

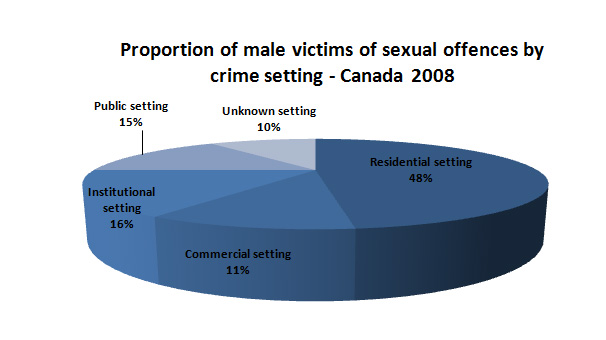

- Nearly half (48%) of sexual offences against men in Canada in 2008 occurred in a residential setting.12

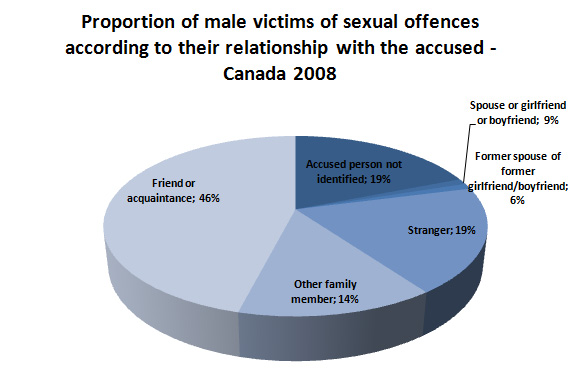

- Most male victims of sexual offences in Canada in 2008 (46%) were assaulted by a friend or an acquaintance.12

Source: MSP 2009

Sexual assault against men in prison

Although it is difficult to determine the real scope of the problem, the World Health Organization (WHO)13 has reported that forced sex regularly occurs among inmates in prison to establish hierarchies of respect and discipline. Moreover, prison staff even play a role in this sexual violence. In fact, sexual assault by prison guards, police and soldiers is reported in many countries. Prisoners may be “forced to have sex with others as a form of ‘entertainment’, or to provide sex for the officers or officials in command”.

Disclosure of sexual assault

Disclosure process

The ability and willingness of sexual assault victims to disclose the abuse they have suffered are key to effective social, medical, psychological and judicial interventions.

- “Disclosure” refers to the process whereby a victim of sexual assault confides in someone, whether a friend or family member or a formal source of support, about a situation that he or she has experienced.15

- However, although victims may disclose sexual assaults, the assaults may never be reported to the authorities.

Disclosure process

Disclosure, especially by children, should be viewed as a multi-stage process that may (or may not) include:16

- attempts to disclose

- denial

- retraction

- reaffirmation

- increasingly detailed descriptions over time

Note: Care must be taken not to interpret a child’s retraction of claims that he or she was a victim of sexual abuse as an indication that the child was lying and making false allegations, because such retractions can be a normal part of the disclosure process. For more information, see the fact sheet on false allegations of child sexual abuse.

Disclosure of sexual abuse experienced in childhood

- Many victims of child sexual abuse delay in disclosing the abuse or never disclose it, thus depriving themselves of the protection and services they need.

Extent to which child sexual abuse is disclosed

- According to best estimates, 33% of sexually abused children disclose the abuse to at least one person before they reach 18 years of age. In addition, 11% of child sexual abuse situations are reported to the authorities.16

- According to a prevalence survey of a representative sample of Québec women in 2008, 26% of those who reported being a victim of sexual abuse during childhood said that they had never disclosed the abuse.17

- Disclosure rates for child sexual abuse are thus quite low and are often said to be just the tip of the iceberg. In fact, only a minority of cases of this type of abuse actually ever come to light.

Roughly 20% of females and 10% of males are sexually abused before they reach the age of 18.

Time taken to disclose child sexual abuse

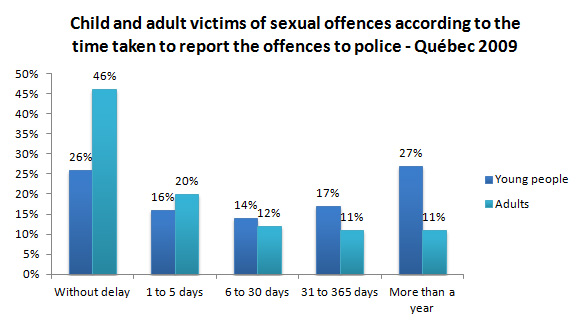

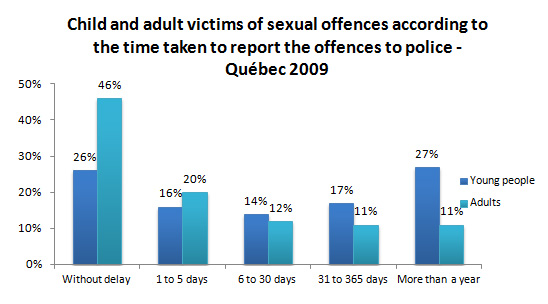

According to the Ministère de la Sécurité publique, children disclose abuse without delay in fewer numbers than adults do. This is due at least in part to the fact that children are more often victimized by family members and may thus be afraid of the consequences disclosure will have for themselves or their family. Furthermore, children are not necessarily able to recognize sexual abuse and talk about it to others.1

- Among the sexual offences reported to police forces in Québec in 2009, those against children were reported on the day of the offence less often than were those against adults (26% compared to 46%).8

- Among the sexual offences reported to police forces in Québec in 2009, those against children were reported more than a year after they were committed, more frequently than were those against adults (27% compared to 11%).8 In addition, 10% of all offences that were reported more than one year later had been committed more than 10 years earlier.

Source : MSP 2009

- According to a prevalence survey of a representative sample of Québec women in 2008, women who reported being victims of sexual abuse in childhood said that they had:

- reported the abuse without delay (within one month) (in 22% of cases);

- disclosed the abuse more than five years later (in 33% of cases).

Disclosure: it can be beneficial, but…

Among the female child sexual abuse victims who were surveyed and who reported that they had disclosed to at least one person the acts they had been subjected to:17

- 66% said that disclosing the abuse had helped them considerably or to some extent;

- 10% said that disclosing the abuse had had a very negative or rather negative impact on them.

These results show the importance of disclosing sexual abuse experienced in childhood. However, they also show that some victims do not necessarily see disclosure in a positive light. The reactions of family and friends can have a favourable or unfavourable effect.18 For more information on how to react to the disclosure of sexual abuse, see the Resources section.

Obstacles to the disclosure of child sexual abuse

Child sexual abuse victims give several reasons for not having disclosed the situation rapidly or for not having disclosed it at all.

-

Some of the reasons are related to feelings of confusion or ambivalence and to fears about the potential consequences of disclosure ― fears sometimes fostered by the perpetrator. To learn more

- Fear of being blamed for the sexual abuse

- Fear of not being believed

- Feeling ashamed or dirty

- Not being sure that what occurred was actually abuse or that it was wrong

- Fear of consequences for one’s family (separation, placement)

- A desire to protect the perpetrator from consequences (e.g. imprisonment)

- Benefits obtained (gifts, advantages, satisfactory relationship)

- Fear that the perpetrator will act on his or her threats

- Fear of stereotypes related to sexual roles or to homosexuality in the case of male victims

- A desire to obey adults (value attached to obedience)

- Certain characteristics of sexual abuse have been associated with whether or not the abuse is disclosed:15,16,19,20,21,22:

-

Relationship to the perpetrator

- Children who have been abused by a stranger or by someone from outside the family are more likely to disclose the abuse and do so without delay.

-

Age of victims

- Most young victims (under 6 years of age) disclose abuse accidentally.

- Accidental disclosure increases with age. Children between the ages of 7 and 13 are more likely to disclose to an adult or a parent, while adolescents disclose primarily to a friend or an intimate partner.

-

Gender of victims

- Compared to girls, boys are less inclined to disclose sexual abuse and to do so without delay, particularly if the abuse occurred during adolescence.

-

Seriousness of the sexual abuse

- Intrafamilial and long-term sexual abuse seem to be disclosed to a more limited extent or disclosed later.

- Sexual abuse with physical violence and injuries is more likely to be disclosed, or disclosed without delay, and be reported to the authorities.

-

Characteristics of victims’ families

- Having access to parental support is associated with disclosure and with prompt disclosure of sexual abuse on the part of children.

- Having a poor relationship with one’s parents is associated with failure to disclose on the part of adolescents.

-

Disclosure of sexual assault experienced in adulthood

- Même si les agressions sexuelles vécues à l’âge adulte apparaissent davantage dévoilées et dans un délai plus court que celles vécues à l’enfance, il demeure qu’une faible proportion d’agressions sexuelles commises envers des adultes seront rapportées aux services de police.

Disclosure of sexual assault experienced in adulthood

- Many of the sexual assault victims surveyed during the 2004 General Social Survey (GSS) on Victimization reported that they had told informal sources of support about the assaults they had experienced during the year prior to the survey.23 The main people they confided in were:

- Friends (72%)

- Family (41%)

- Co-workers (33%)

- Doctors or nurses (13%)

Reporting of adult sexual assault to police

- According to the 2004 General Social Survey (GSS) on Victimization, less than about 1 in 10 sexual assaults experienced during the year prior to the survey had been reported to police.23

- The 2004 GSS data show that, among the categories of crime considered during the survey, sexual assault is the one that was least reported to police during the year prior to the survey.23

| Violent crimes experienced during the year prior to the survey | Proportion of crimes reported to police |

|---|---|

|

Robbery

|

47%

|

|

Assault

|

40%

|

|

Sexual assault

|

10%

|

- In the case of sexual assaults against adults reported to police services in Québec in 2009, the majority were reported without delay (46%), while only 11% were reported more than one year later.8

Source : MSP 2009

Obstacles to the disclosure of adult sexual assault

- According to the 2004 General Social Survey (GSS) on Victimization, about 1 in 10 sexual assaults were reported to police within the year after they occurred, Victims gave various reasons to explain why they did not notify the police :23

- They felt the incident was not important enough (58%).

- They had dealt with the incident in another way (54%).

- They felt it was a personal matter (47%).

- They did not want to get involved with the police (41%).

- Certain characteristics of sexual assault seem to have an impact on whether or not it is reported to police. According to the 2004 General Social Survey on Victimization: 23

- Sexual touching was less likely to be reported to police (6%) than sexual attacks (22%).

Last update: October 2016

- Ministère de la Sécurité publique du Québec (2012). Infractions sexuelles au Québec : Faits saillants 2010. Québec: Gouvernement du Québec. (Available in French only)

- Collin-Vézina, D. and Tourigny, M. (2011, September). Les taux d’agression sexuelle au Québec et au Canada : Que comprendre des données issues des études d’incidence et de prévalence ? Paper presented at the Congrès international francophone sur l’agression sexuelle-CIFAS. Montreux, Switzerland. (Available in French only)

- Higgins, D.J. and McCabe, M.P. (2001). Multiple forms of child abuse and neglect: Adult retrospective reports. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 6: 547-578.

- Tourigny, M., Hébert, M., Joly, J., Cyr, M. and Baril, K. (2008). Prevalence and co-occurrence of violence against children in the Quebec population. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 32(4): 331-335.

- Tourigny, M., Hébert, M., Daigneault, I., Jacob, M. and Wright, J. (2005). Portrait québécois des signalements pour abus sexuels faits à la Direction de la protection de la jeunesse. Research report. Sherbrooke: Université de Sherbrooke. (Available in French only)

- Trocmé, N., Fallon, B., MacLaurin, B. and Neves, T. (2003). What is driving increasing child welfare caseloads in Ontario? Analysis of the 1993 and 1998 Ontario Incidence Studies. Child Welfare, 84: 341-362.

- Trocmé, N., Fallon, B., MacLaurin, B., Daciuk, J., Felstiner, C., Black, T. et al. (2005). Canadian Incidence Study of Reported Child Abuse and Neglect – 2003: Major Findings. Ottawa: Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada.

- Ministère de la Sécurité publique du Québec (2011). Statistiques sur les agressions sexuelles au Québec 2009. Québec: Gouvernement du Québec. (Available in French only)

- Tourigny, M. and Baril, K. (2011). Les agressions sexuelles durant l’enfance : Ampleur et facteurs de risque. In M. Hébert, M. Cyr, and M. Tourigny, eds., L’agression sexuelle envers les enfants Tome 1 (pp. 7-42). Québec: Presses de l’Université du Québec. (Available in French only)

- Wolfe, V.V. (2007). Child sexual abuse. In E.J. Mash and R.A. Barkley, eds., Assessment of Childhood Disorders (4th ed.) (pp. 685-748), New York: Guilford Press.

- Collin-Vézina, D. and Turcotte, D. (2011, June). L’abus sexuel envers les enfants au Canada : les victimes, les auteurs et les contextes. Paper presented at the Colloque international sur l’exploitation sexuelle des enfants et des conduites excessives. La Malbaie, Canada. (Available in French only)

- Statistics Canada. (2010). Gender Differences in Police-reported Violent Crime in Canada, 2008. R. Vaillancourt. Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics. Catalogue no. 85F0033M, no. 24.

- Jewkes, R., Sen, P. and Garcia-Moreno, C. (2002). Sexual violence. In E.G. Krug, L.L. Dahlberg, J.A. Mercy, A. Zwi and R. Lozano-Ascencio, eds., World report on violence and health (pp. 147-181). Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Statistics Canada. (2010). Gender Differences in Police-reported Violent Crime in Canada, 2008. R. Vaillancourt. Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics. Catalogue no. 85F0033M, no. 24.

- Ullman, S. (2003). Social reactions to child sexual abuse disclosures: A critical review. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 12(1): 89-120.

- London, K., Bruck, M., Ceci, S.J. and Shuman, D.W. (2005). Disclosure of child sexual abuse. What does the research tell us about the ways that children tell? Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 11(1): 194-226.

- Baril, K. and Tourigny, M. (2010, October). Dévoiler l’agression sexuelle : Qui sont les victimes qui dévoilent et quels sont les impacts d’un dévoilement? Paper presented at the Congrès de l’Association internationale des victimes de l’inceste. Paris, France. (Available in French only)

- Ullman, S. (2010). Benefits and barriers to disclosing sexual trauma: A contextual approach. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 11: 127-133.

- Paine, M.L. and Hansen, D.J. (2002). Factors influencing children to self-disclosure sexual abuse. Clinical Psychology Review, 22: 271-295.

- London, K., Bruck, M., Wright, D.B. and Ceci, S.J. (2008). Review of the contemporary literature on how children report sexual abuse to others: Findings, methodological issues, and implications for forensic interviewers. Memory, 16(1): 29-47.

- Hébert, M., Tourigny, M., Cyr, M., McDuff, P. and Joly, J. (2009). Prevalence of childhood sexual abuse and timing of disclosure in a representative sample of adults from Quebec. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 54(9): 631-636.

- Allagia, R. (2005). Disclosing the trauma of child sexual abuse: A gender analysis. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 10(5): 453-470.

- Brennan S. and Taylor-Butts, A. (2008). Sexual Assault in Canada, 2004 and 2007. Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics. Catalogue no. 85F0033M, no. 19.